FATEMA NOOH: "WE CAN ALL TEACH EACH OTHER OUR HISTORIES."

Fatema Nooh, like many moving from the Gulf to Europe, was seeking a different perspective on the world. After following a friend’s advice: “you only really see the inside of your environment once you take a look at it from the outside” she enrolled into a design course, packed her bags and moved to a small village in Germany. One of her first realizations was the huge misconceptions about Arabs and the Middle East and in particular, women from the Middle East. Nooh’s experience in Germany evolved symbiotically with her to the direction her art practice has taken, which is to view things from a different lens. She felt herself standing out amongst the small population which led her to question why these misrepresentations of Arabs are so prevalent and how can she change them? She decided to take a direction in her work that would allow her to show an inner ‘truth’ about people, bridging the gap between misrepresentation and understanding. Through projects like Under The Veil (2016) and More Than Strangers (2016), she uses visual communication to combat fabrications made by the mainstream media and forces a conversation about difficult topics. BANAT is proud to welcome an artist who is actively in conversation about the representation of women and refugees and who's goals are to inform people and help them find an understanding and acceptance of their differences.

What made you decide to move to Germany?

I decided to study in Germany because, as one of my close friends once told me, you only really see your own environment once you look at it from the outside. Coming to Germany has enabled me to meet many different people from many different backgrounds that have many different views, it has really showed me how the misconceptions of the Middle East are so wide. I would get questions like: can you talk to the male members in your family? I found that very interesting because we as a people in the Middle East, view the West like they are more progressive than we are. So when I came to Germany I realised that we have a very good view of the West, while they don't have a good view of the Middle East, so I tried to focus all my projects on that. I live in a village that basically has absolutely nothing, people looked at me in a different way not like in Berlin or in Cologne, where people get to see tourists from the Middle East. There’s about 30,000 or so inhabitants so before the ‘refugee crisis’ they didn't really get to see many people and many women from the Middle East.

Tell us about your project ‘Under the Veil’, how did it begin and what was your process?

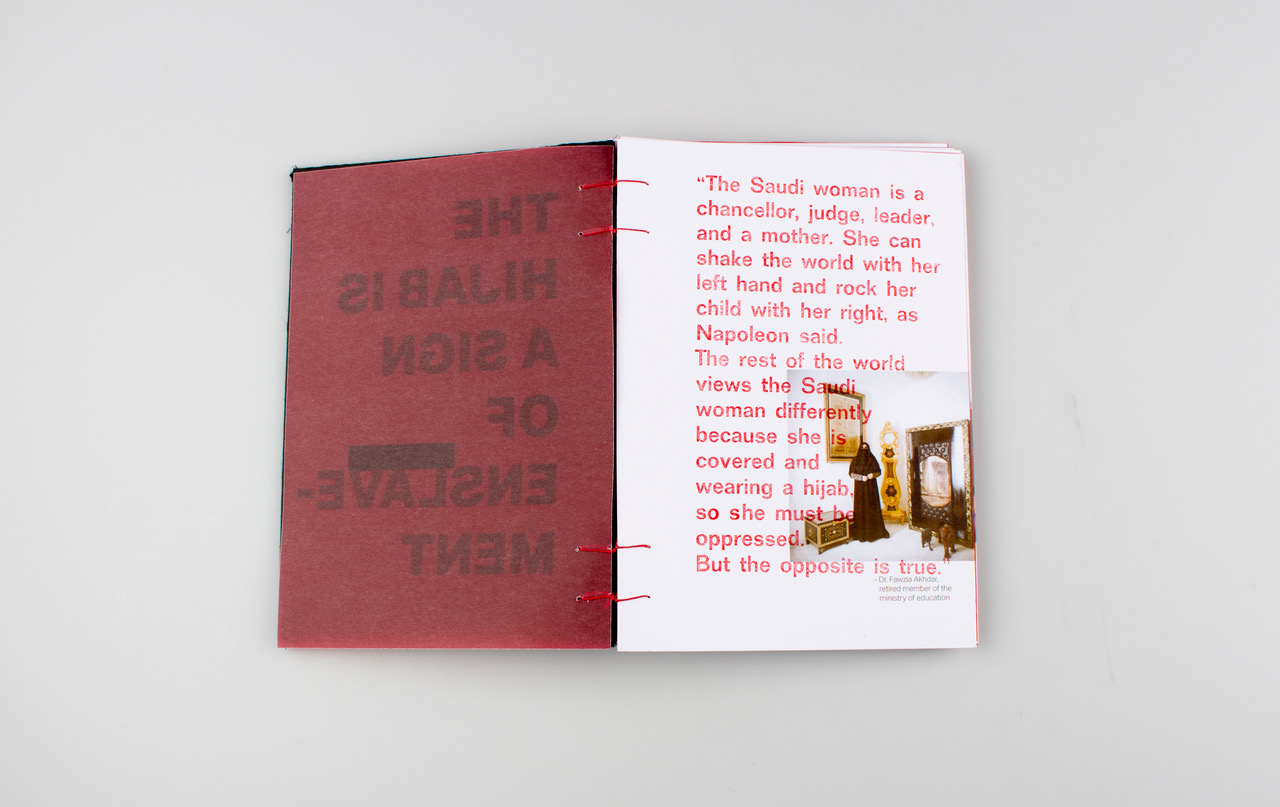

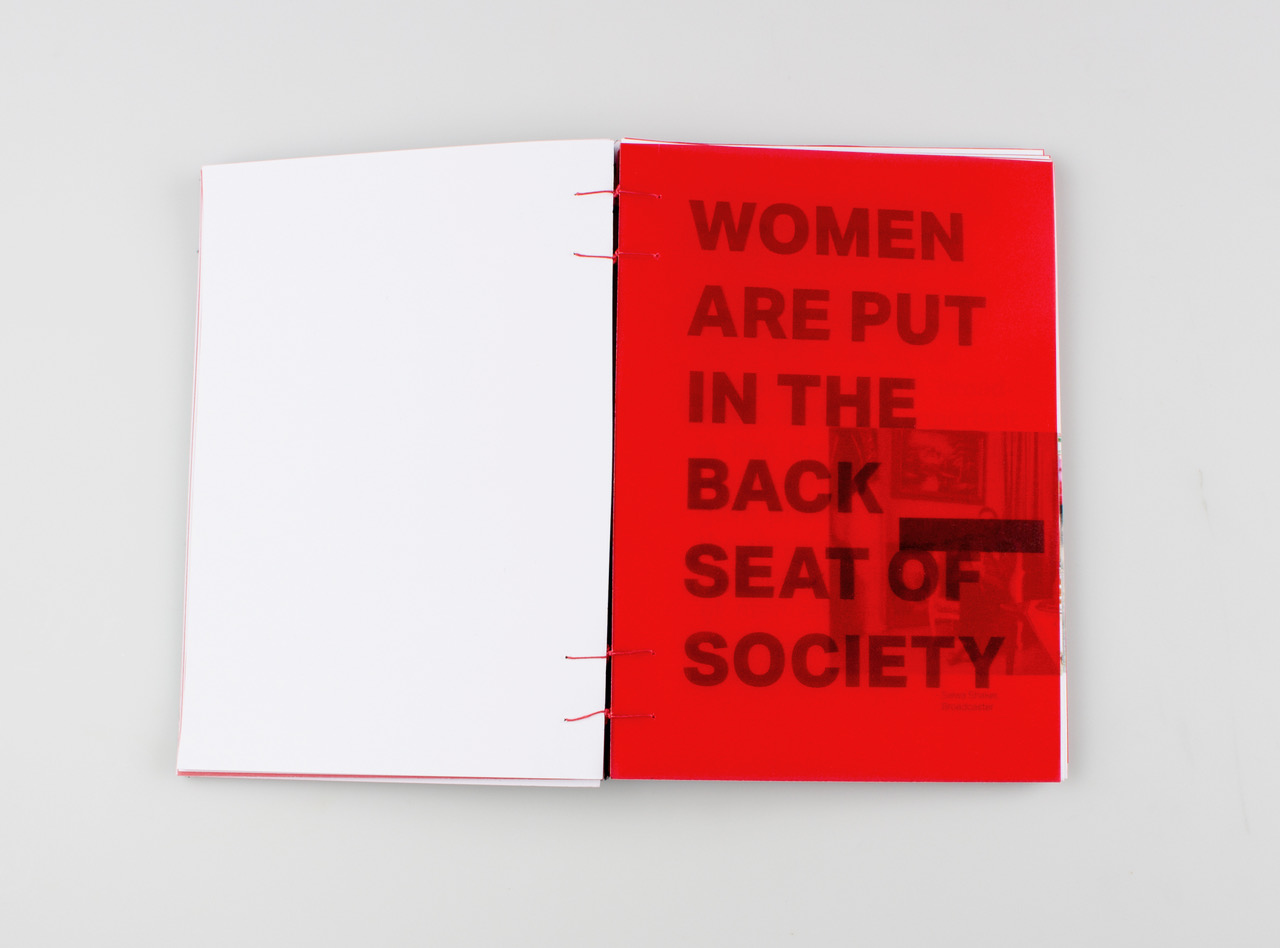

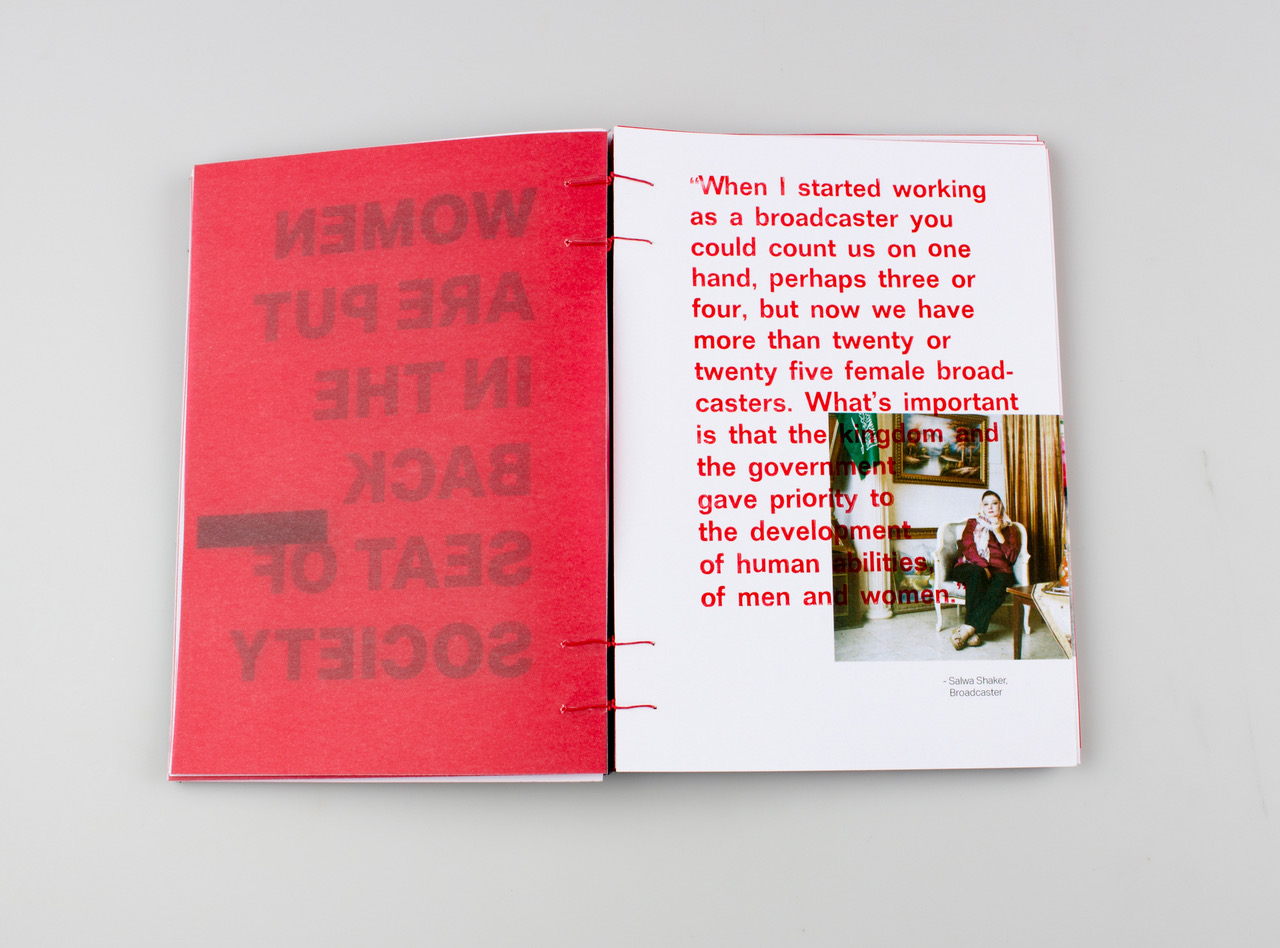

I wanted to show that there are many different opinions and there are many different backgrounds to everyone. We don't have to agree with something to be able to live with it, for example the hijab is very controversial here in the West. Many westerners view it as a symbol of oppression and I just wanted to show them that every woman has her own reason. Maybe there are women who are oppressed but there are women who choose to cover because they believe in it. Some women think of it as a symbol of cleanliness, some do because they believe in it religiously and some because of fashion. In any case, just jumping to conclusions is not the right way to go about things in life generally.

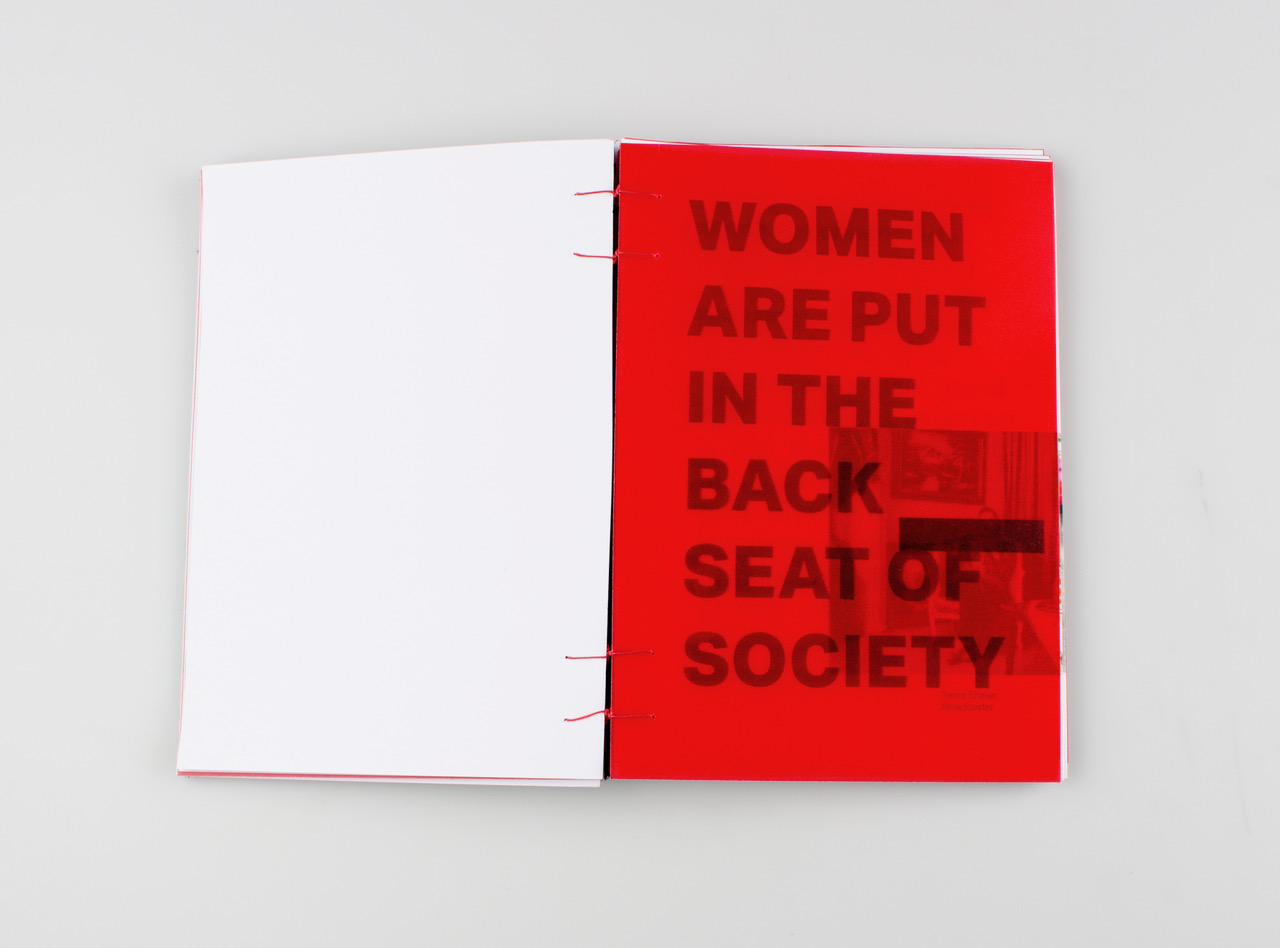

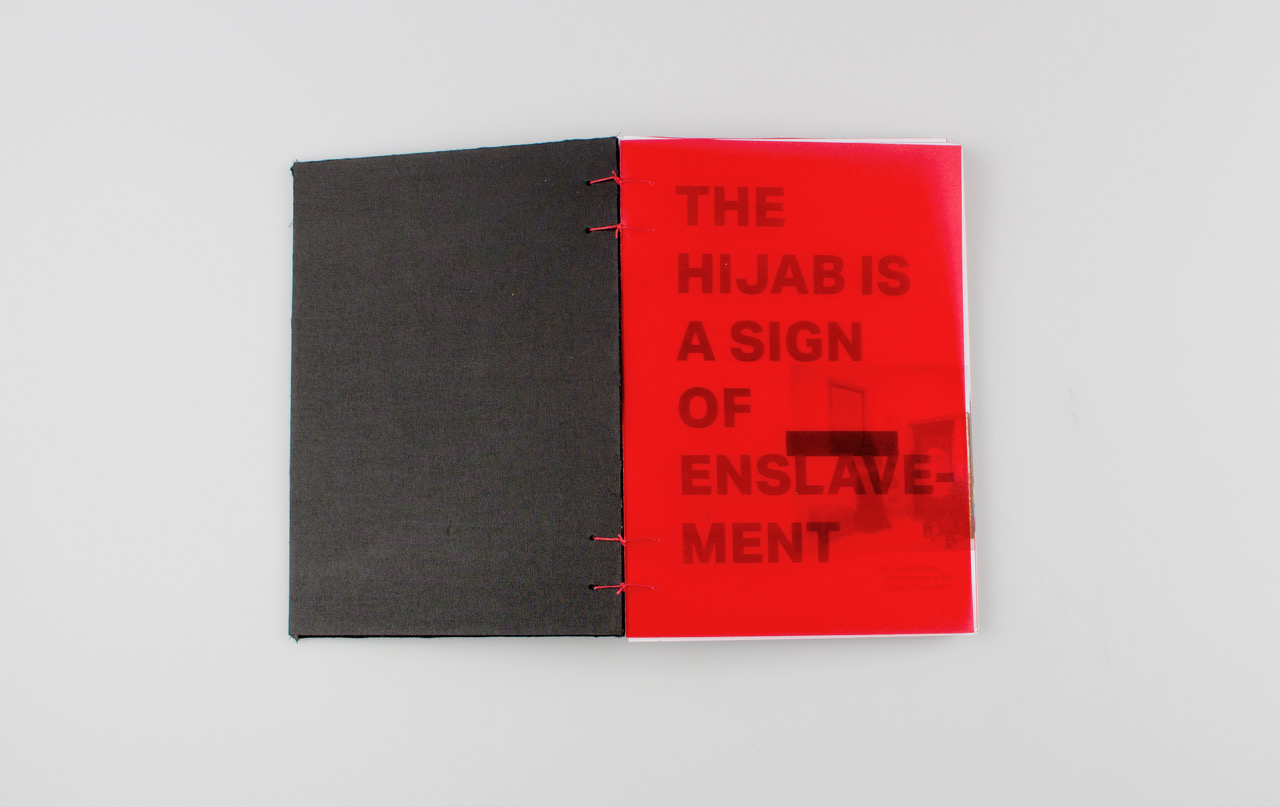

I collaborated with a photographer named Ziyah Gafić who has a project called ‘Unveiled’, he is from Bosnia and he went to Saudi Arabia to document women who live there. I used his photographs and the quotes of the women from his documentary in my book. I then took it to the printing lab and tried different techniques. The reason why I decided to go with the letter press is because it's not perfect. I felt like that technique emphasised the message that I wanted to come through. The ink on the letters will never show perfectly just like we as human beings aren't perfect either and our perspectives on things can be biased. The print on the transparency sheet, which are quotes that I took from news interviews and articles written about women in the Middle East I printed digitally because it's perfect and so it's loud you know? It's in your face! I wanted to show that it's not giving you space to talk, it's just saying that this is the way it is. Those women aren't saying their opinion is the only opinion they’re just saying that this is ‘their perspective on things’ and people in the West need to understand that what they see is not always the truth.

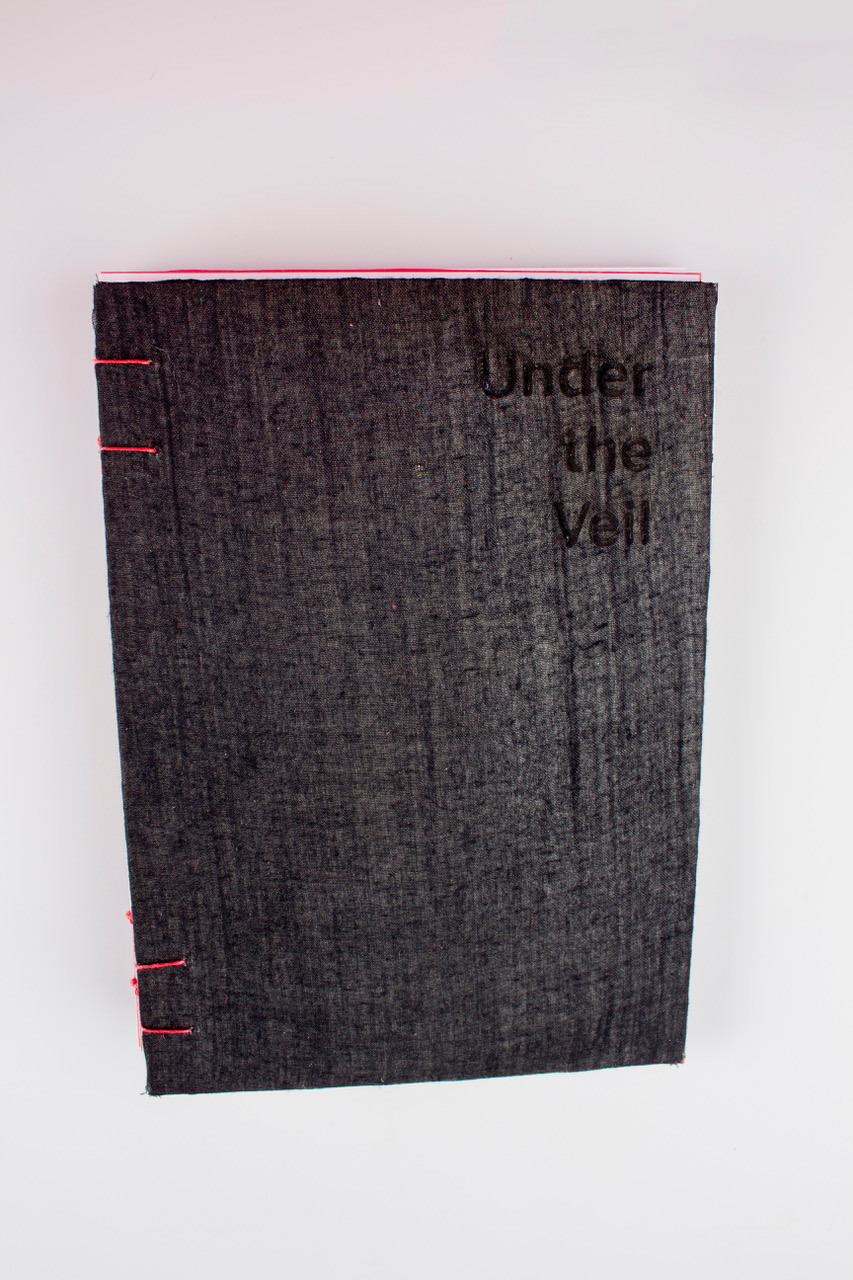

The book is a hardcover book and the title is laser-engraved in the cardboard and I chose to cover the book with the black hijab. First of all you see the other kind of veil, where the media veils the truth, once you take those two layers off you read what the women say. The women that are included in the book are from many different backgrounds. They look very different and they all fought in a way that doesn't have anything to do with hijab. Some women fight because they want to reach somewhere in life. They have a goal in life that they want to reach and the hijab isn't necessarily what's restrictive. People in the West say that women in the Middle East are oppressed because of the hijab but what I want to tell them is: it is our choice and it's in our hands to speak up against it, it's not their job to force us to do something because that in itself, is also a form of oppression.

What were the responses to the project?

I had a couple of professors come up to me and tell me they didn't know it felt like that. A student from China came up to me and we sat for four hours discussing how she had never understood the situation the way I did and that just the other day she was reading an article saying there’s an organisation where you can donate so they can help women who are veiled. I was telling her that it's not the right way to think about it and it's just a personal choice like any religion. Maybe some women are oppressed but it's not fair of us to just generalise all women from the Middle East and say things like: you're all oppressed because of that one piece of cloth that you wear. It's as if a girl wears a long sleeve shirt or a short skirt, it doesn't and shouldn't mean anything.

What did you learn from this project?

The first time I went back home - since being in Germany - I remember sitting with my dad and I was telling him how I think it's amazing how Germany recovered from the World Wars and how the people are open to new ideas, that they're open to listening to what I have to say, and I was telling him that I wish we (Bahrainis) were like that. I wish that we could just sit around and talk about anything even if it goes against what we believe in - he didn't say anything at the time. Last Christmas though, when I went back home, I was sitting with him and I told him I realised that it's not fair of me to compare Germany to Bahrain. Our history is not the same, Bahrain is a younger country than Germany is. In comparison to many other countries, our development in the GCC was quite fast. When my dad talks about when he was young, he used to always tell me things like: ‘the beach used to come up to here’ and ‘all of those buildings weren't there’ and that was less than fifty years ago! It’s not fair of me to go back home and say we're not as good as they are. I realised that the best thing I can do is live in Germany, experience and learn and then return to Bahrain and try to make a difference. At the end of the day Bahrain is my home and no matter how much I love the opportunities in Germany, I can still seize those opportunities and take them back home without demanding they exist in Bahrain as well. When I first decided to study graphic design, a lot of people came up to me said: yeah but what kind of a job is that? What they don't realise is that I can use my ability to visualise a message. I want people to understand that my choices in life are mine. If my ideologies don't harm you then, where's the problem? I think we can all co-exist with our different beliefs and we can all benefit each other. We can all teach each other our histories. I know many people who are half-American, half-Saudi, half-British, half-Ukrainian, ‘half-Western’, ‘half-Middle Eastern.’ Those people manage to bring together two completely different societies and I think that is very beautiful.

Tell us about your project ‘More Than Strangers’.

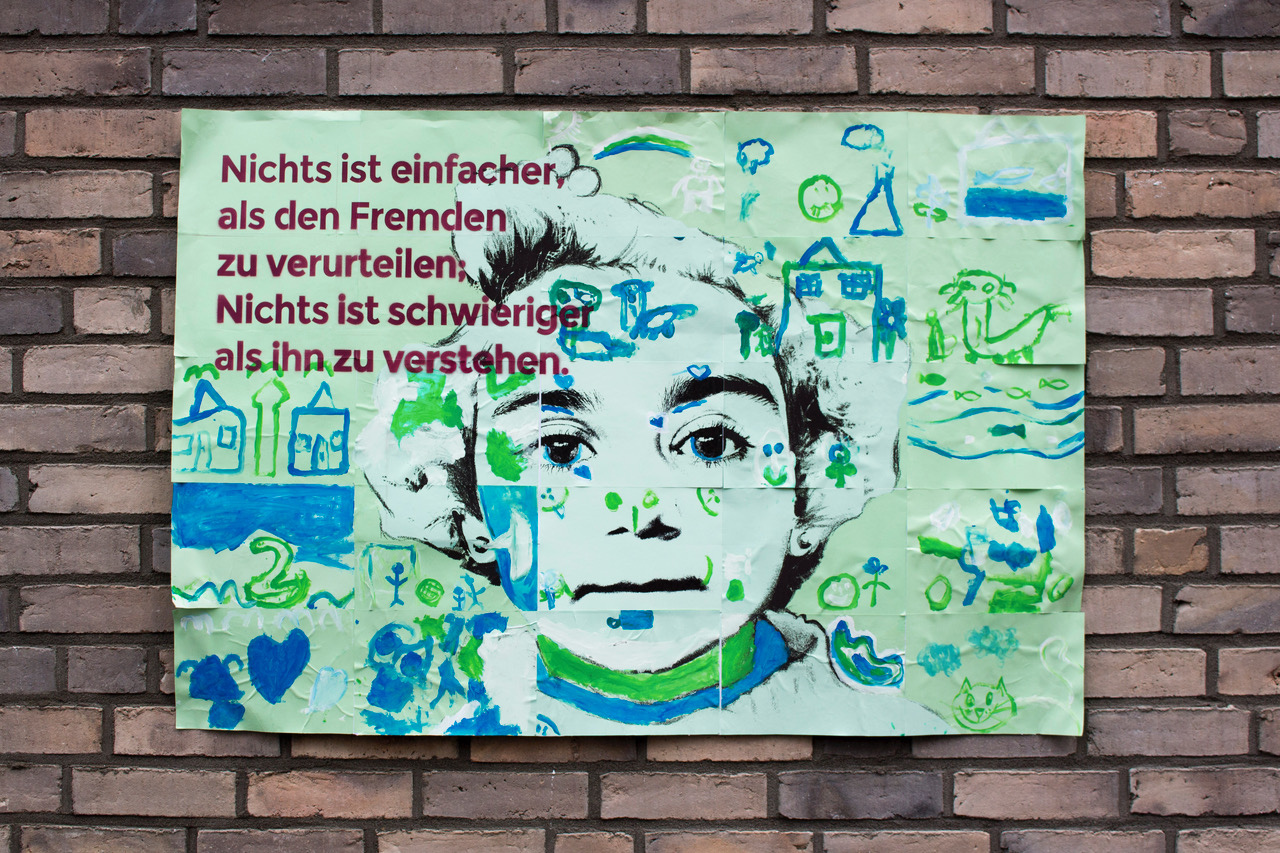

"More than Strangers" is a ‘refugee project,' (in collaboration with Nada Abouzeid). There is a quote in the final poster which translates to: "Nothing is easier than to denounce a stranger and nothing is harder than to understand him." The notion was to bring a clear message to everyday people, someone just walking down the street. We worked at the refugee centre here in our village as translators. We help the refugees understand what's going on and the rules of the country and society. As we were working with them we got to play with the kids, we got to sit with the elderly, we got to talk to the Germans in charge as well. We went to town hall meetings, meetings where everyone from the town was attending. When we were sitting with them, all the refugees wanted to do was to fit in, they were scared, they didn’t speak the language, they look different, their history is different, they’d just experienced trauma. Some of them literally couldn't tell us their story because of how harsh it was. The idea for “More Than Strangers” mostly came from sitting with the kids because the elderly wanted to talk politics, they wanted to talk about where they were, where they came from, what they wanted to do. Some of them just wanted things to go back to normal in their country so they could go back. When we sat with the kids, they had this energy, this energy that filled the whole camp and that is an understatement because they gave more than that, they gave the camp life. Everyone there was just tired, they just wanted some place to sleep or a job but the kids they wanted to talk to everyone. They didn’t want to talk in Arabic, they wanted to learn German.

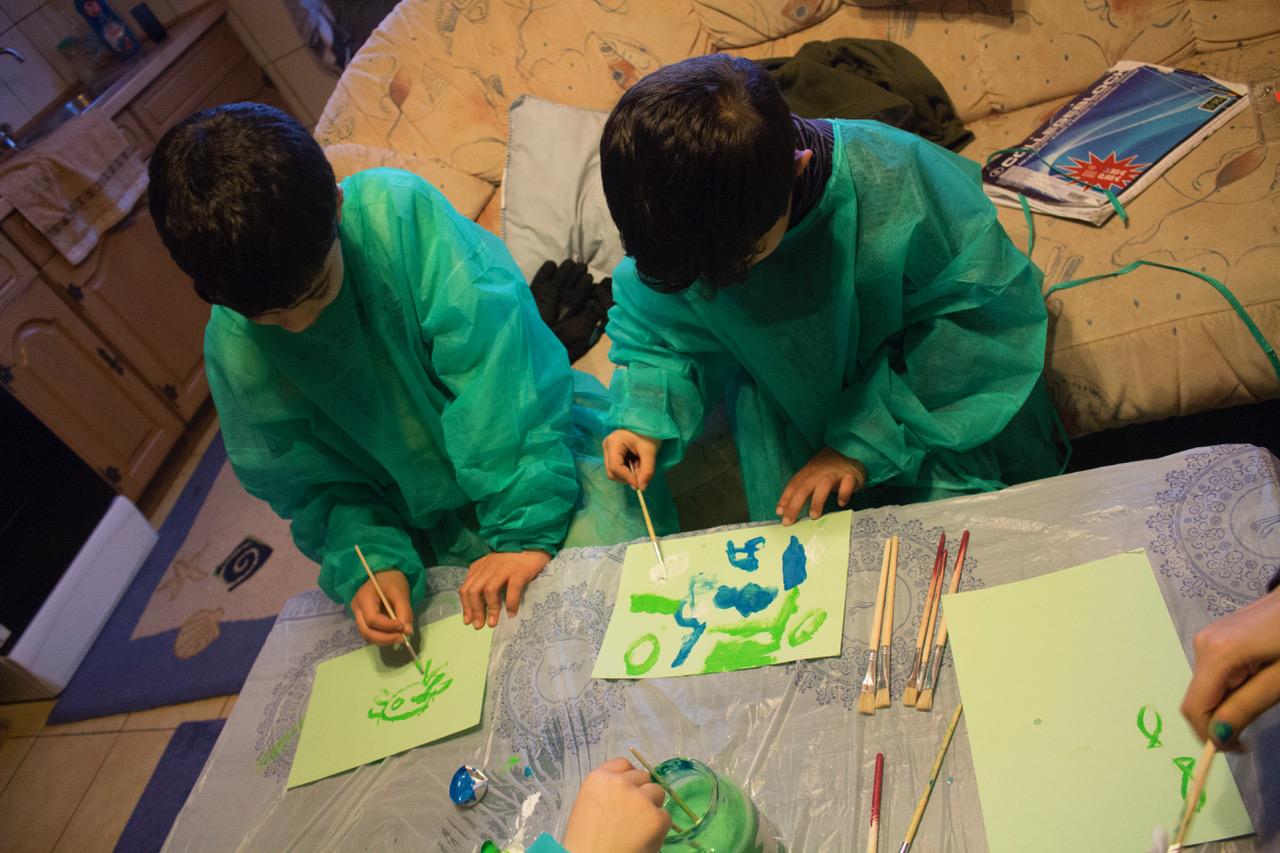

We organised a trip where they got to meet kids their age and they were so excited. They didn’t speak each other's language but they just ran around the playground and every time they wanted something they couldn't explain in German, they'd run to us and ask us: "How do I say this in German?" From that, we organised a play date twice a week. We would give them a topic to talk about every time or to draw a number of things and the things that they came up with were so diverse and so beautiful! Some of them were still stuck in the war zone and their drawings were all about that. Some of them just wanted a happy home so that's all they wanted to draw.

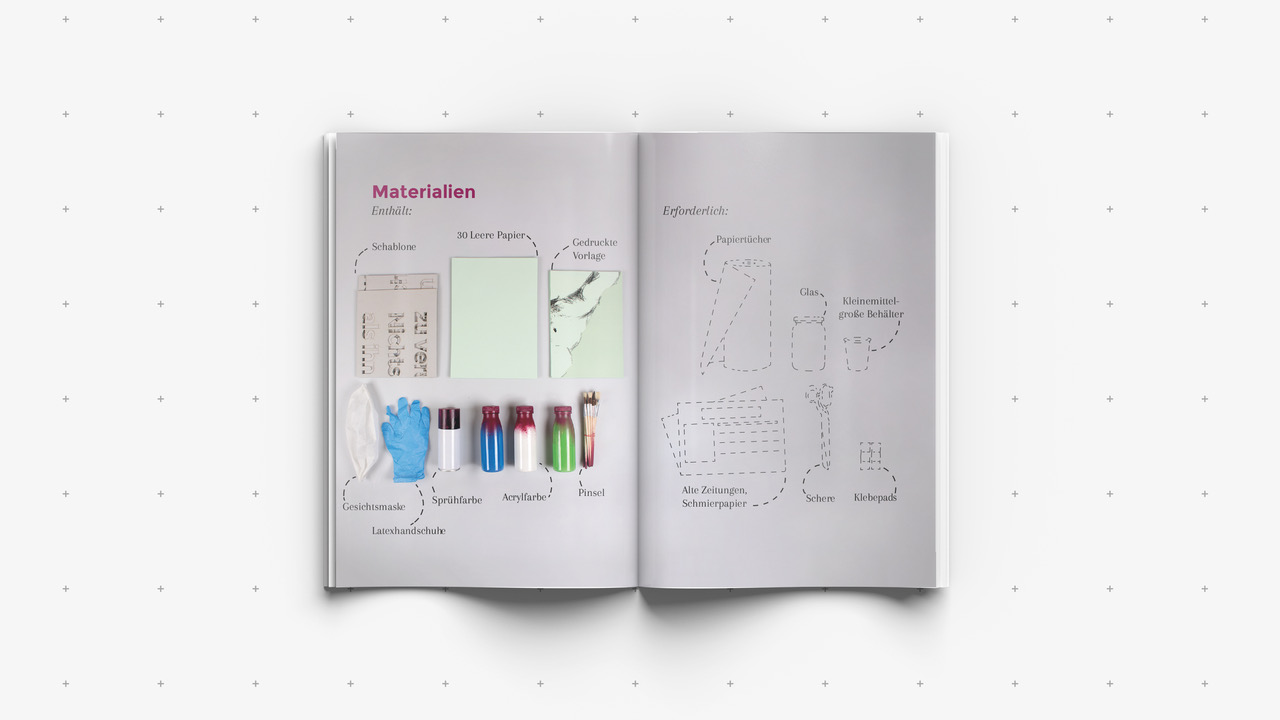

We made this ‘kid basket’ where we provided everything they needed to make their art. We gave them the topic of "home", anything that's related to home, their idea of a home, what they wanted, or what they had, or anything that reminds them of home. The kids each had a paper that had a line so that when the papers were put together they made a face. We found that was a really good outlet for them because they used the German language, they put all their feelings on the paper and they never wanted it to end. Finally, when they had all finished we'd put it all together to see the full picture and once they saw the full picture they wanted to show it to everyone! To them it was individual work but also teamwork at the same time. Then we spray painted it and we put it outside on the wall. From afar you just see these random drawings and when you get closer you see a face and when you get even closer you see the detail of each individual child. You can't differentiate the German kids drawings from the refugee kids drawings because, kids like all human beings, have the same idea of home as a safe place. That was very refreshing for everyone who got to see the poster and for the kids themselves. We wanted to create a sort of hallway for the refugees to interact with the outside world that they live in yet, they are in this camp where they have to be until they get their permit to leave.

The reason why we called it "More than Strangers" was because we wanted people to realise that we're only strangers because we haven’t got to know each other. A new bus would come every day at eight and you would sit with the refugees until 2AM and after that you wouldn't feel like they were strangers anymore. Once we start communicating, once we interact we aren't going be strangers anymore. Our backgrounds are different but what we want to achieve in life is practically the same. That’s the reason we chose the age-group we did because that's as pure as it can get. Just simply what makes us happy without any agenda and those kids, they didn't care that they’d experienced war, they only cared about their fresh start. This one young guy literally lost his whole family and when he came down from the bus we took each family in to register them and so each group or family had a translator and someone from the red cross. He didn't have anyone and so I told him we couldn't register him alone because he was a minor and he didn't know what to do because he didn't have anyone with him. But this other family overheard him and they took him in!

What are your thoughts on feminism?

I used to say that I didn't want to call myself a feminist because people associate it with negativity, that feminists just want everything for women and nothing for men. I don't believe that anymore though, I believe that feminism is about providing equal opportunities for everyone and it's up to the person to decide what they want to do with that opportunity. I think it's unfair for women wearing the hijab to be viewed as closed-minded and oppressed. All my sisters wear a hijab, my mom wears a hijab! I can talk to them about anything that's going on in my life whether it's something that's religious or not. Personally I think that it's a personal choice and every time someone talks about it I think: don't judge a book by it's cover, don't judge a person by their cover! If I see a woman who's completely naked on the street and I saw a woman who's completely covered, it doesn't tell me anything about their personalities. Other than this woman is covered, and this woman is naked. I think it's absurd that we just generalise.

I have friends that are not wearing the hijab that are more religious than my friends who wear a hijab. It doesn't represent anything, it's not a symbol of religion. I dislike that people think that being religious equals being closed-minded.

What do you think of BANAT as a platform?

When I first saw BANAT I thought it could be a platform to share ideas and have someone to talk to. I thought that could be somewhere where my ideas, my perspective on things and how I like to use my design can be seen without any concern. That's what I expect from BANAT. Somewhere where we get to express ourselves and not be afraid. I don't want to oppress an issue I truly believe in because I don't want people to misunderstand it. Let them misunderstand it and come up to me and I'll explain it to them. I’m reminded of something that happened after “Under The Veil” project, this student came up to me and she said: I have something to ask you but I'm scared because I don't want to offend you, but I don't really understand it. I just want to hear it from the perspective of a person that comes from that society. I told her to go ahead and she told me she had read this article that was saying that the Shia and the Sunna in our society are against each other. She was so apologetic while she was asking me. I actually respected that she asked me because she didn't jump to a conclusion. She didn't accuse me of anything. She came up to me and asked me for clarification and I really respected that. I respected that she wanted to talk about it and I think that's what I expect from the platform. Where we just get to talk, even if it's something that's a bit controversial.

Follow & Support Fatema Nooh:

online portfolio

instagram

interviewed by Sara Safwan